My Mongolian musical education

(This piece was originally published in The Lifted Brow #17: The Music Issue. Thanks Sam Cooney!)

In July 2010 I went to Mongolia knowing almost nothing about the country’s music. There was a documentary about Mongolian throat-singing I could’ve watched, but I didn’t; besides, I wasn’t going there to learn about throat-singing. Now, nearly three years later, and through no conscious planning of my own, I find myself able to add the title of ‘Freelance unpaid Mongolian music producer’ to my long and dubious job history.

My introduction to Mongol pop…

…occurred in a shower in a hostel in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s capital. The plastic shower unit had a built-in radio, waterproof , and a ceiling that was about head-height. If it wasn’t for the radio I would’ve just hunched over and scrubbed uselessly at my overripe armpits, but the banging Eurovision-esque tunes blasting from the radio and its red and green graphic equaliser lights bopping up and down in time with the bronchial — yet strangely tuneful — vocals made me want to bop up and down too. I bashed my head on the ceiling. The ceiling flapped up like the lid of a toilet seat. This made me dance harder. When my travelling companion Tama had a shower, I could hear him dancing too.

Who is the best rapper in Mongolia?

On a thirty-hour bus ride from Ulaanbaatar to the town of Mörön in northern Mongolia, Tama struck up a halting conversation with a Mongolian teenager sitting next to him. The kid had a shaved head and was dressed in the international hip-hop style: baggy jeans and black hoodie. We played him some Jay-Z, which he already knew and loved, but also some more obscure stuff (‘obscure’ to a rural Mongol teen who lived in Mörön) like Roots Manuva, Thirstin’ Howl III and the classic Soundbombing II album. Whenever the boy was really getting into a track, Tama would skip to something new; the boy would look startled and frown, then politely nod in time with the new song.

In return, the youth played us some Mongolian hip-hop on his fakey iPod. The production was surprisingly professional, with proper scratching and sinister high-pitched loops in the Wu Tang style. It was almost of a US hip-hop standard, and not enjoyably laughable like, say, Filipino or Aussie hip-hop. Apart from the odd “punk fake shit motherfucker”, the lyrics were incomprehensible to us, but they had a good harsh growl to them, and the Mongolian language’s numerous glottal vomit-moments were well suited to the art of spit-boxing. I asked the teen who was the best rapper in Mongolia. “Opozit,” he said incredulously, as if that was a very stupid question.

Songs that got stuck in my head

The bus ride got bumpier. Our heads hit the ceiling, repeatedly. To take the edge off we popped a couple of Valiums and washed them down with a mouthful of Chinggis Khaan vodka. Tama shoved a headphone in my ear and played me the album Daft Punk Live in New York, which I had never heard before. The Mongolian countryside jolted by outside. I was a bit smashed; I was sort of having a great time; it was sort of like a disco shower, definitely memorable. Now whenever I listen to that Daft Punk album, particularly the live version of ‘Robot Rock’ — with its shredded industrial organ riff that sounds like a hexagonal record made of concrete skipping (in the best possible way) — it makes my scalp tingle and takes me right back to the sloppy darkness of that bus, and slams my head into the ceiling.

Three nights later we were resting up in the lakeside town of Khatgal. My left forearm was sore after an afternoon spent wrestling two drunken middle-aged men on the grass outside our tourist ger (a round white felt tent that Russians call a yurt) and now it was raining. Tama and I had assembled our mountain-bikes in Mörön and cycled like mad things to Khatgal for Naadam, a two-day holiday of “Manly Sports”. We were expecting crazy parties and wild dancing — Schoolies by the Lake, Mongol-style — but there was nothing of the sort. Luckily, we were so munted from the 100-kilometre cycle that this was a relief rather than a disappointment. Here is what happened next, as I describe it in the just-published book version of our misadventure:

“The rain stopped around midnight and the sudden silence woke us up.It didn’t keep us awake, though – theMongolian disco music that belched forth within seconds of the rain stopping and that didn’t let up until dawn kept us awake. From damaged speakers that seemed to be located just underneath our beds, the same song blared forth, over and over: a melancholy-yet-jazzy synth, running low on batteries and overpowered by a tragic male voice that boomed, warbled and trampled all over the melody with the word ‘Chinggis’ ringing out again and again. The song evoked a once-handsome cowboy who was now rather chubby, standing tall and lonely on a mountain ridge, lamenting the loss of his Marlboros. Like all good pop, the song was both heartbreaking and infinitely trite.”

There are a couple of lines from that song I will never be able to un-remember, even though I can’t pronounce them properly or tell you what they mean.

As me and Tama cycled across northern Mongolia, marvelling at the ridiculous views and sometimes not talking for hours, random songs would bubble out of my subconscious into my inner ear and stay stuck on repeat. For the first couple of days it was the extremely motivational ‘Road to Nowhere’ by Talking Heads, except it went more like this:

We’re on the ro-o-ad to Mörön, come on inside

Takin’ that ri-i-ide to Mörön, we’ll take that ride

Then as the towns dropped away and we were very much in the middle of nowhere, a confused version of ‘Olso in the Summertime’ by Of Montreal arrived:

Mon-gol in the summer, zang

There aren’t ee-ven any streets

Everyone’s off herding goats and drinking Chinggis

When the riding grew difficult, which was often, I’d find myself singing Jay-Z’s ’99 Problems’ through gritted teeth. Most of the Jiggaman’s crack-slingin’ travails felt wholly unrelated to my own struggles with gelatinous canned meat and biting flies, until one afternoon just east of Jargaltkhaan when a Mongolian police officer riding a decrepit motorcycle pulled us over. He invited us to stay with in his family ger for the night, but I was terrified that he would somehow smell the extremely small amount of half-dried wild cannabis leaf I had secreted in one of my pannier bags and frog-march us off to Ulaanbaatar’s infamous underground jail, so we politely declined.

Throat-singing

We didn’t meet any throat-singers. Possibly this is because we were in the north near the Siberian border, and I think that throat-singing is more a phenomenon of Mongolia’s Gobi Desert south.

Musical xenophobia

After over a thousand kilometres of off-road shenanigans, Tama and I made a pit-stop in Ulaanbaatar. We spent a dazed afternoon in a DVD and CD store, trying and failing to agree on a movie to watch on our rest day. Also from the book:

“I wandered into the music CDs section and my eyes alighted on a guy called bYPXAHA X3N3X 3OBNOrOO, whose close-cropped hair was photographed in statesmanlike black and white. X3N3X was standing on the patriotic Mongolian steppe wearing black combat fatigues and casually holding a large, bright-red (colourised) flag. The edge of a swastika armband was just visible. On the back cover X3N3X was standing behind a lectern, his armband more prominent, orating from a little black book — and it didn’t look like he was reading out phone numbers. This was the cultural output of Dayar Mongol, Mongolia’s version of the One Nation Party, whose anti-Chinese racism was spruced up with retrograde Nazi iconography.”

I wanted to buy the bYPXAHA X3N3X 3OBNOrOO CD just for the weirdness and badness of it, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. Tama got a couple of hip-hop CDs: Opozit, and a tough-looking guy with a beanie, a goatie and an unreadable name. Both albums sounded pretty good, as long as you didn’t care to know what they were rapping about.

Last night a Mongol DJ saved my life

Twenty-four hours and seventy or eighty kilometres later we were in Gorkhi-Terelj National Park. We had found a tourist ger campthat specialised in making Dutch-style gouda cheese, and were experiencing something dangerously close to relaxation. I volunteered to cycle into the town of Terelj, five kilometres distant, to get supplies (i.e. Russian petrol for our stove; as much rice and chocolate as I could carry; any rogue vegetables I could find). On the way into town I became utterly lost in a swamp, and was despairing of ever finding Terelj, when I heard a faint, bassy rumble. I pushed my bike through the swamp towards the noise. It got louder and louder, until I could hear vocals. Saved by Mongolian pop music! I followed the familiar harmonic howling all the way into town, and it never sounded so good, before or since. Someone must’ve been getting married that night, someone rich, because the music blasted across the Gorkhi-Terelj National Park all night long, and I came to a fuller and more complete understanding of the concept of ‘noise pollution’.

Throat-singing (II)

On the final morning of our ride to Mörön, I woke up pretty much recovered after a heinous bout of food poisoning the day before, probably brought on after eating the dried fermented milk of a horse given to us by a ten-year-old cowboy with hands almost as dirty as mine. I was extremely happy not to be vomiting, so happy that I climbed to the top of a nearby hill and sung, at the top of my lungs, the only Mongolian song I knew by heart:

Gooh she-shish-ah-mo hoo ee hooooo

Goooooh shish she nae hoo neeh hooooooo

Gooh shi-shish shee mooo

Ooo eh hee ah ooooo

Aaah shish shee ah hee oooooooo

I didn’t transliterate the lyrics like that in the book, although now I wish I had.

Bright lights, medium-sized city

Back in Ulaanbaatar after our ride, Tama and I went on a somewhat obligatory trip to a strip club. (Weeks ago, huddling under a tarp during a lightning-and-hail-storm, being able to visit a strip club had seemed like the height of both luxury and urbanity. Now it just seemed a bit trashy, but we had a couple of days to kill before our flight home). The place was dark, cavernous and almost entirely empty, save for a drunken Chinese businessman who all at once bought us three beers each then lurched off, leaving us to try and drink them before they went flat. The music was a mix of dirty US club hip-hop (‘Get Low’ by Lil’ Jon and the Eastside Boyz, that kinda thing) and very, very bad techno. In the far corner of the club there was a pole, but no one was dancing on it. Tama got a half-hearted lap-dance from a girl in white underpants and I covertly filmed it until the bouncers came over and told me to please stop. We sipped at our many beers.

After half an hour or so, Outkast’s ‘Hey Ya!’ came on. One of the off-duty strippers, fully-although-skimpily clothed, came over and asked me to dance, without asking for money. We walked awkwardly onto the empty dance floor and did some tame booty-dancing about half a metre from each other. The girl told me that I was a good dancer. I think I said, “I know.” Then the song finished and she said, “Thank you” and I said, “Thank you” and we both sat down in opposite corners of the darkened room.

According to the Lonely Planet there’s a nightclub in Ulaanbaatar with a nine-metre high statue of Josef Stalin in the middle of the dance floor. We never made it there.

The best documentary I have seen about contemporary Mongolian music

Back in Australia, I was suffering acute Mongolia withdrawals when I met a dude called Benj Binks. Benj was making a documentary called Mongolian Bling. He had visited Mongolia in 2007 and became obsessed with the Mongolian hip-hop scene, which is thriving, possibly because downtown Ulaanbaatar looks like one giant housing project and reaches minus 35 degrees Celsius in midwinter, making oversized hoodies practical as well as fashionable. Mongolian Bling premiered in 2012 and is an amazingly intimate chronicle of the lives and times of a handful of Ulaanbaatar-based rappers, including a lovely young mother-of-one called Gennie who, when she’s not making mutton dumplings, totally rips the mic apart. The doco also features extended interviews with Gee, the goatie’d guy whose CD Tama had randomly bought in Ulaanbaatar. Gee is an excellent rapper and very good at keeping it real, but in recent years he has also written some fiercely xenophobic songs. Like ‘Hujaa’, which translates roughly as ‘Chink’:

The whores you bought, the ministers you bought

They’re not Mongols – they’re halfbreeds

Mongolia is growing and will not be tricked by the Chinese

This is pretty harsh stuff, but at the same time, it’s not like rap and racism are strange bedfellows.

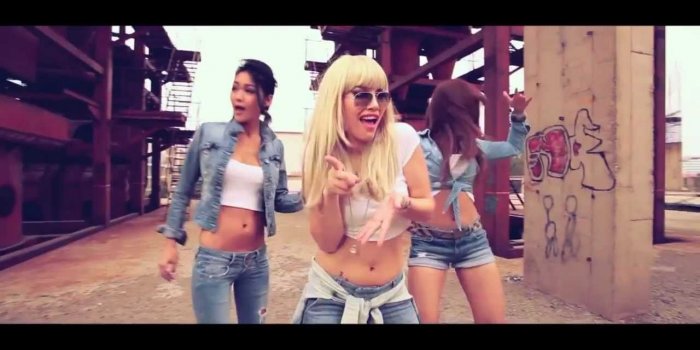

The oddest name we saw for a Mongolian girl band…

…is ‘Kiwi’ (in Cyrillic, Киви; I’m not sure how it’s pronounced). They’re like the Mongolian Spice Girls except they’re all trying to be Lady Gaga. Their 2007 song ‘Hotline’ includes the winning and non-offensive lyrics:

Hotline baby, come on dial now

Hotline baby, this is the time

I want to be with you now-ow-ow

This is not khreally a crime

To the best of my knowledge, Kiwi have never toured to New Zealand and they are yet to make an appearance at Camp A Low Hum. Someone needs to sort this out.

Freelance Mongolian music production, moron-style

Over the last few months I have been helping my Kiwi friend and fellow moron Puck Murphy make some little video clips to go with the book of the blog of the bike ride, Mörön to Mörön. At first we wanted to use Mongolian songs ripped fromYouTube — this is how Puck and I discovered the wonders of Kiwi/Киви — but trying to get in touch with Mongolian record labels to discuss track licensing has been complicated to say the least. It would help if I could speak or read Mongolian, or if I was living in Mongolia, or if I knew anything about the process of licensing tracks.

Luckily, Benj ‘Mongolian Bling’ Binks has come to the rescue. Benj has become something of a playa in the Mongolian music industry, and is going to try to get us the rights to one track by Kiwi and another by Gee (hopefully we’ll sample a non-racist bit). Benj also put me in touch with a great Mongolian musician called Bukhu. Bukhu lives in Sydney; he sings a mean throat-song and fiddles a mean horse fiddle. His website (www.horsefiddle.com) includes a version of ‘Waltzing Matilda’ that sounds more like ‘What a Wonderful World’. Bukhu has let us use a couple of his tracks, and also kindly pointed out that the samples of Naadam bökh wrestling commentary in one of our videos were not from Naadam at all, but a different national wrestling holiday, and provided us with links to more appropriate bökh wrestling commentary to sample.

MongoLazer

Meanwhile, Puck and I have also begged New Zealand musician Conrad Wedde (of The Phoenix Foundation) to make us some short songs in the modern Mongol style, with a bit of Antipodean mong thrown in for good measure. For example, Mongolian synth melodies + Major Lazer ‘dancehall robo sex’ franticness = MongoLazer! This is a good start, but it’s not enough, since it’s the vocals that really give you that hit of weird and wonderful Mongoliana. So, how to fake that? In one case, I took the liberty of writing some lyrics:

Meat in a can, meat in a can

Stupid tourists love eating meat in a can

Meat!

The original plan was to convert this on Google Translate and get the computer to speak it for us. But although Google Translate features translations for 64 languages, including Azerbaijani and Urdu, it doesn’t do Mongolian. So instead I used my Mongolian phrasebook to do a crude translation:

Laaz makh, laaz makh

Teneg juulchin khairtai laaz makh

Makh!

But while this would sound fine (i.e. like exotic gibberish) to English-speakers, it would sound not fine (i.e. like non-syntactical gibberish) to those fluent in Mongolian. So I emailed Bukhu, and although he found my request a little odd, he humoured me and translated the lyrics properly:

Laazalsan makh, laazalsan makh

Teneg juulchidiin ideh durtai laazalsan makh

Makh!

Next we worked out that, thanks to a glitch in Google Translate, we could paste those Mongolian words into the ‘translate from’ field and select ‘English’. Then, in the ‘translate from’ field, whatever language we tried to translate it to would fail. However, it would speak the untranslatable words in the accent of the language we chose. But of course there was no Mongolian in Google Translate, which meant no Mongolian accent, which meant we needed to think laterally. Mongolians often speak English with a heavy Russian accent — Kiwi sound like a Russian band when they sing in English — but the Russian accent is too unambiguously Russian to be helpful here. Kazakh would probably have been perfect, but Google Translate doesn’t feature that either.

I remembered reading somewhere that Mongolian is considered by some linguists to be part of the controversial ‘Ural-Altaic language group’, which apparently spawned such linguistic anomalies as Korean, Hungarian and Finnish. The ‘Ural-Altaic’ theory has been soundly disproven, but even so I tried making the computer speak Mongolian in a Hungarian accent, and it was pretty good; it had pretty much the right drawl and rasp to it. The Finnish sounded good too, with a poppy sing-song lilt that Conrad described approvingly as ‘bounce’, as well as plenty of Slavic hoick. (The Korean didn’t work.)

So thanks to the miracles of modern technological impedimenta, I now have a six-second piece of Mongol-ish pop in the style of Kiwi (Киви), made by a Kiwi (NZ) musician, with lyrics written by a New Zealander living in Melbourne and translated by a Mongolian living in Sydney, sung by Finnish and Hungarian Google robots, then jammed through Autotune and dumped onto YouTube.

These days, whenever I get pangs of Mongolia-homesickness — which is often — I console myself by firing up YouTube and watching random Mongol music videos. My favourite artists include Zorigoo, who dresses like a post-punk eco-hunk and combines old-school throat-singing with cutting-edge (or at least late 90s) techno, and in the clip for ‘Mt Kharkhiraa’ plays a double-necked horse fiddle like a Mongolian Jimmy Page. But Zorigoo is nothing on Maadai, who rocks out in nightclub and desert alike in expensive suits and cravats and is never to be seen without his trademark wraparound sunglasses. Sound familiar? Well, Maadai’s song ‘Khar sarnai’ (‘Cool eyes’) was released on 12 October 2011, a full nine months before ‘Gangnam Style’ changed the face of modern music forever. Is Maadai the inspiration for Psy? Let’s not rule it out. ‘Cool eyes’ might only have 12,622 views to ‘Gangnam Style’s 1.5 billion hits, but still — Maadai takes himself more seriously, which makes it funnier.

And even though I hadn’t heard of Zorigoo or Maadai back in 2010 when Tama and I were flogging ourselves through the forests and bogs of northern Mongolia, now when I listen to their glottal syncopation it takes me back to a happy place. A place where I was young, and free, and didn’t have a care in the world — except where my next can of emergency meat was coming from. And how I was going to keep up with Tama up that endless hill. And where the hell we actually were. And how to get that song, that accursed jangling song, out of my head, when it’s just so very catchy:

Gooh she-shish-ah-mo hoo ee hooooo

Goooooh shish she nae hoo neeh hooooooo …